I am the Lorax. I speak for the trees. I speak for the trees for the trees have no tongues.

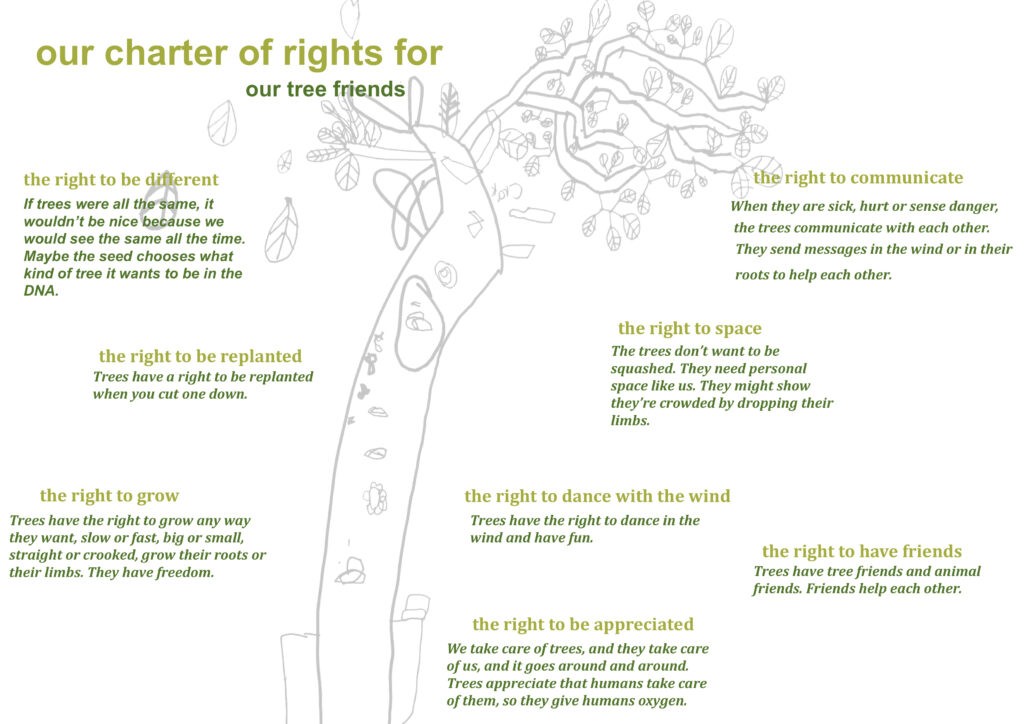

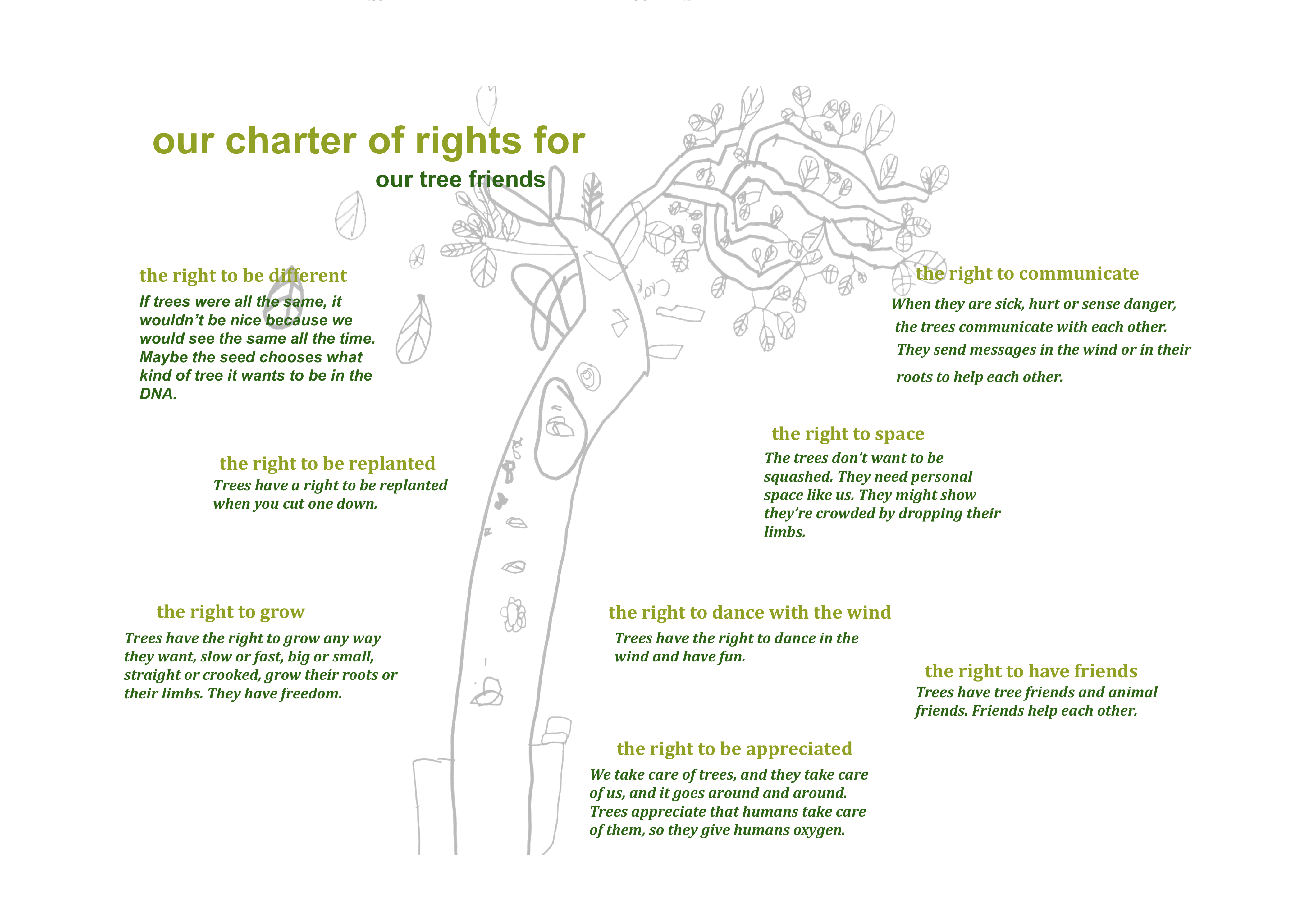

The titular character of Dr. Seuss’ children’s fable, personifying environmental activism in the face of human despoliation, begs the question about whether the natural world has ‘rights.’ At ELC, we strive to develop ecologically literate global citizens attuned to the interdependence of humans and our environment. By reflecting on their own rights, the children are able to bring empathy and compassion to their consideration of the natural world they inhabit and gain a deeper understanding of the now burgeoning ‘Rights of Nature’ movement they are witness to, and participants in. In 1974, the law professor Christopher Stone was one of the first to call for natural objects or ecosystems to have legal standing and protective guardianship. In his ‘The Great Work’ (1999), Thomas Berry, the cultural historian, identified the need for ‘Earth Jurisprudence’, and built on the idea that nature and its processes have inherent value that transcend their service to humanity, they should be conceived as subjects with intrinsic merit independent of humans: ‘Trees have tree rights, insects have insect rights, rivers have river rights, mountains have mountain rights. So too with the entire range of beings throughout the universe.’ This ‘Rights of Nature’ movement has now spread across the globe with legal breakthroughs granting personhood and rights to, for example, the Wanganui River in New Zealand in 2017, the Amazon River ecosystem in 2018, and the Magpie River in Canada, 2021. ELC children were moved by issues of justice and respect for the natural world to draft their own Charter of Rights for Trees: